Making metadata

Metadata has been in the media in recent years, as governments around the world seek increased access to information about our online activities. If you want an frightening insight into what the metadata you phone collects can reveal about your life, have a look at what the ABC reporter Will Ockenden discovered.

But metadata isn’t new. It’s just data about data – the sort of thing you might find in old library card catalogue (remember those), or even printed on the spine of a book. This video gives a quick introduction to the basic characteristics of metadata.

In the GLAM sector we often talk about ‘collection data’ and ‘metadata’ interchangeably. As the video notes, metadata is itself data, so there’s no point getting hung up on the distinction. The point is that metadata is what we use to describe, manage, control, and discover collections. It’s the data we gather or create about the things in our collections. Increasingly, of course, we create and manage collection metadata in digital form, using a wide variety of digital systems and databases, but metadata isn’t dependent on any particular technology – a caption is metadata whether it’s stored in a collection management system or scrawled on the back of a photo.

Why is metadata important for cultural heritage collections? The Open Metadata Handbook provides a nice, brief introduction to the uses of metadata. The National Information Standards Organization (NISO) has published a more detailed guide, and it’s worth reading the sections on ‘Metadata in everyday life’ and ‘Metadata in the cultural heritage world’.

Portfolio alert! What’s the value of metadata? Read the sources linked above and write 5 dot points on the importance of metadata to the GLAM sector. Make it convincing!

Seeing standards

One important use of collection metadata is discovery – metadata enables us to search collections by keyword, or find everything created in a particular year. Trove works by bringing together collection metadata from lots of different systems, so you can search across hundreds of collections at once. But there’s a problem. What if the systems use different formats for date, or different names for their data fields? Does ‘title’ in one database mean the same as ‘name’ in another? For metadata to be really useful, it needs a certain level of consistency. We need some agreement on what we’re describing and how.

This is where standards can be useful. Standards define shared practices and meanings.

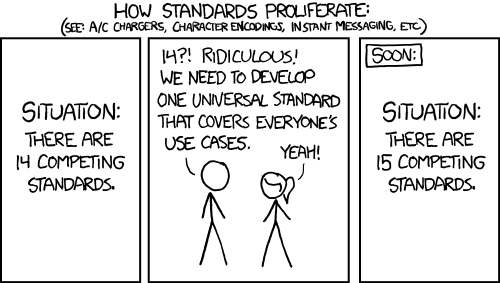

We’re lucky in the cultural heritage sector because we have LOTS AND LOTS of standards! (Ok, so maybe that’s not a good thing?)

There’s a lot of truth to the XKCD cartoon (which must be shown as part of any discussion about standards).

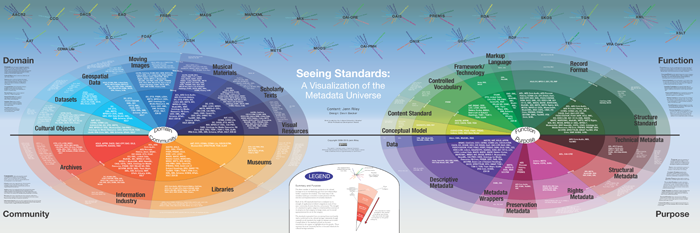

Too see the results of this in the GLAM sector see Jenn Riley’s visualisation Seeing Standards.

Yep, at least 105 different standards are being used in the cultural heritage sector! Eeek! But fear not! You’ll probably only ever encounter a small number of these, and in many cases you’ll be using them without even knowing it.

Standards support the description of collections in a variety of ways.

- Forming frameworks – Standards can define the basic practices which constitute a field of activity. For example the National Standards for Australian Museums and Galleries set out the responsibilities, expectations and activities that make a museum a museum. There are similar sorts of standards for archives. These sorts of standards can be used to review current practice or frame organisational policies.

- Defining descriptions – Standards can define what information that should be captured about collections and how it should be structured. For example the General International Standard Archival Description (ISAD(G)) sets out the basic principles guiding the arrangement and description of archives.

- Enabling exchange – Standards can describe how collection information can be packaged and shared to support aggregation or reuse. For example Dublin Core sets out a basic set of terms that are widely used to share collection information.

Another form of standard are authority lists or controlled vocabularies. These may be simple, flat lists of terms, or complex hierarchies. The widely-used Subject Headings from the Library of Congress are an example of this sort of standard. For a visualisation of the complexity of the the subject headings system see the LoC Subject Headings Galaxy.

As I mentioned, most of the time you’ll be using standards without even knowing it. For example, the Small Museums Cataloguing Manual ‘accords with Benchmark A2.4.2 of the National Standards for Australan Museums and Galleries’. The standard is being used to give context and authority to the manual.

Sometimes standards are used in the design of tools. The archival management system AtoM (or AccessToMemory) is designed to meet the requirements of the ISAD(G) standard. The core fields in Omeka are based on the Dublin Core standard, so even without thinking about it users are guided towards a consistent descriptive framework.

Here are a few standards that you might meet. Don’t panic! The details aren’t important at this stage (though you might want to get to know Dublin Core as we’ll be using it in coming weeks). I just want you to get a sense of the sorts of standards that are used in the cultural heritage sector so that you’re never tempted to create your own!:

- Dublin Core – for general collection discovery

- METS (Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard) – for capturing metadata within a digital library, often combined with ALTO to represent information about digitised objects.

- ALTO – for describing the structure or layout of text objects, such as the position of articles on a newspaper page.

- TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) – for representing the structure and content of digital texts.

- CIDOC-CRM – a framework for representing cultural heritage information

- EAD (Encoded Archival Description) – for preparing archival finding aids

- EAC-CPF (Encoded Archival Context: Corporate bodies, Persons, Families) – for describing people and organisations associated with archival collections

- OAI-PMH (Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting) – for sharing cultural heritage collections in a harvestable, machine-readable form

The National Library of Australia has a page which lists the standards involved in the management of their collections.

Portfolio alert! Imagine you have responsibility for a collection of recorded music (both digital and analogue). Now look through the Seeing Standards glossary for relevant standards. Write a minimum of 100 words on which standards you think would be most useful to you and why.

Standards are not standard

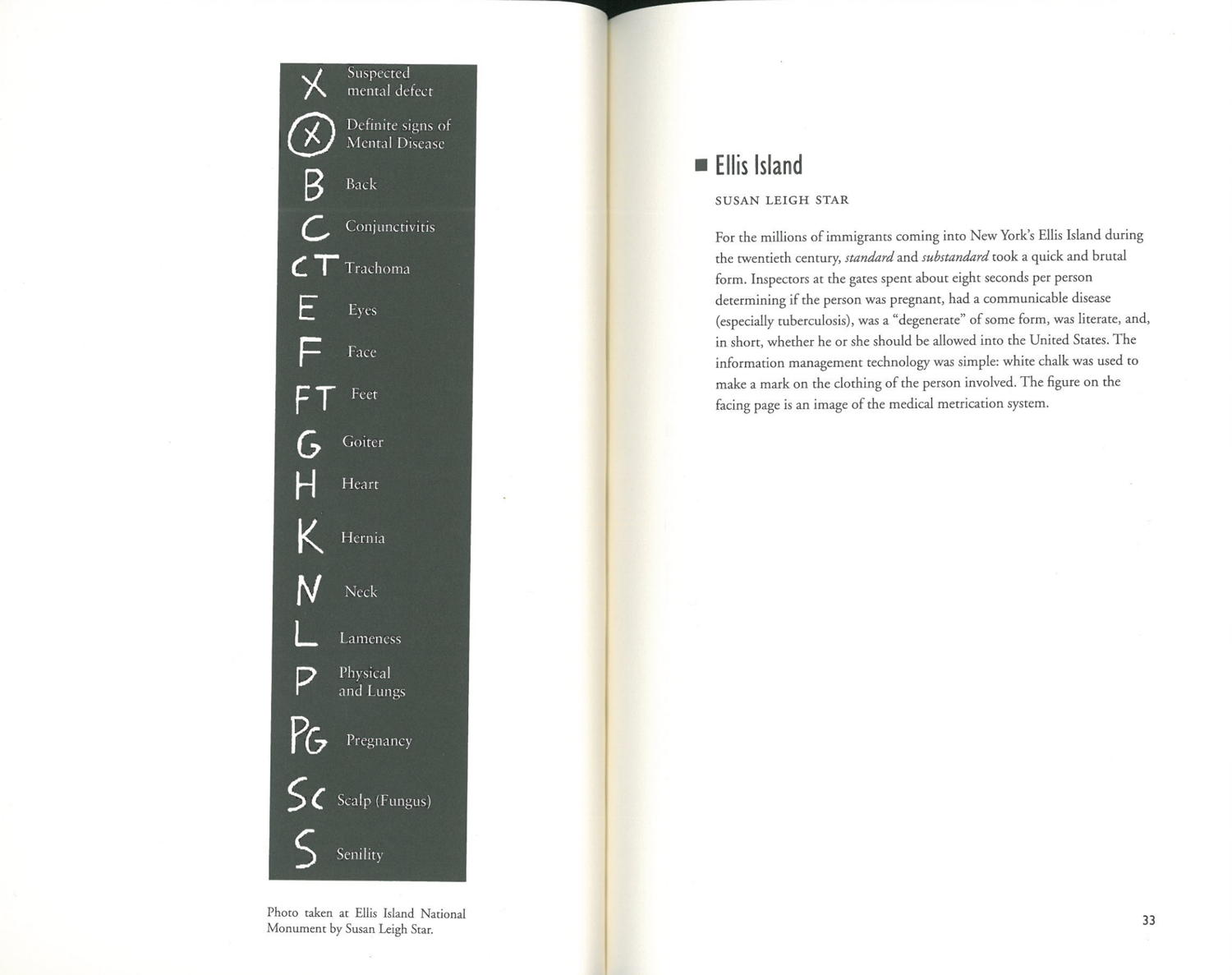

But standards and authorities aren’t neutral, they reflect a particular world view. The image below shows a standard system used in the classification of immigrants to the USA in the early twentieth century. Based on this system, inspectors would pass judgement on people hoping to enter the country.

Although standards attempt to fix a set of rules or categories, they are still part of history. Read the following short articles:

- A brief history of homophobia in Dewey Decimal classification

- Controversy over the use of terms ‘alien’ and ‘illegal immigrant’ in library subject headings

In both cases we can see that the systems themselves have evolved over time in response to community attitudes. It’s important to recognise that standards can, and probably should, change.

Standards creating organisations can also seek to involve and represent a range of perspectives. For example, the National Library of New Zealand is developing a set of Maori Subject Headings that reflect a Maori world view. In one of my favourite articles about archival description, Wendy Diff and Verne Harris talk about the possibility of a ‘liberatory descriptive standard’ – a standard that opens up possibilities for the redistribution of power in archives. Their article is pretty dense, but it’s certainly worth reading – if you find it hard to get into, skip to the final two sections ‘Deconstructing description’ and ‘Unmasking the titular’. A liberatory descriptive standard, Duff and Harris argue:

…would strive for an openness to other tellings and re-tellings of competing stories… Things which do not fit the boxes would not be either discarded or manipulated to size… And, as has already been suggested, the boxes would be given optimal flexibility and permeability. Holes would be created to allow the power to pour out. (p. 285)

Portfolio alert! How can we put holes in our metadata boxes? After reading the resources linked above, I want you to write a short (minimum of 100 words) reflection on how the development and use of standards in cultural heritage might be opened up to new forms of collaboration, to new ways of sharing power and authority. What ethical questions do we need to confront? Who do we need to involve?

Digital systems

Once we move into the digital environment our collection descriptions become data – we can not only read them, we can search and manipulate them in ways that that are not possible within the analogue environment. Digital collection management improves efficiency, encourages standardisation, extends discovery, and enables reuse. We can do much more with the same set of descriptions.

But there are also new challenges! Often we have to deal with different varieties of data spread across multiple systems.

For example, even if your descriptions are captured in digital form, that doesn’t mean you can automatically make them available to the public. Management systems are often completely separate from the systems used to deliver collections online. Digital images of collection objects can also be stored outside of collection management systems in specialised repositories (such as Digital Asset Management Systems). What about the content of exhibitions, help documentation, or information about users? All of this might be connected in some way to your collection descriptions, but it can managed quite separately. Things can get messy.

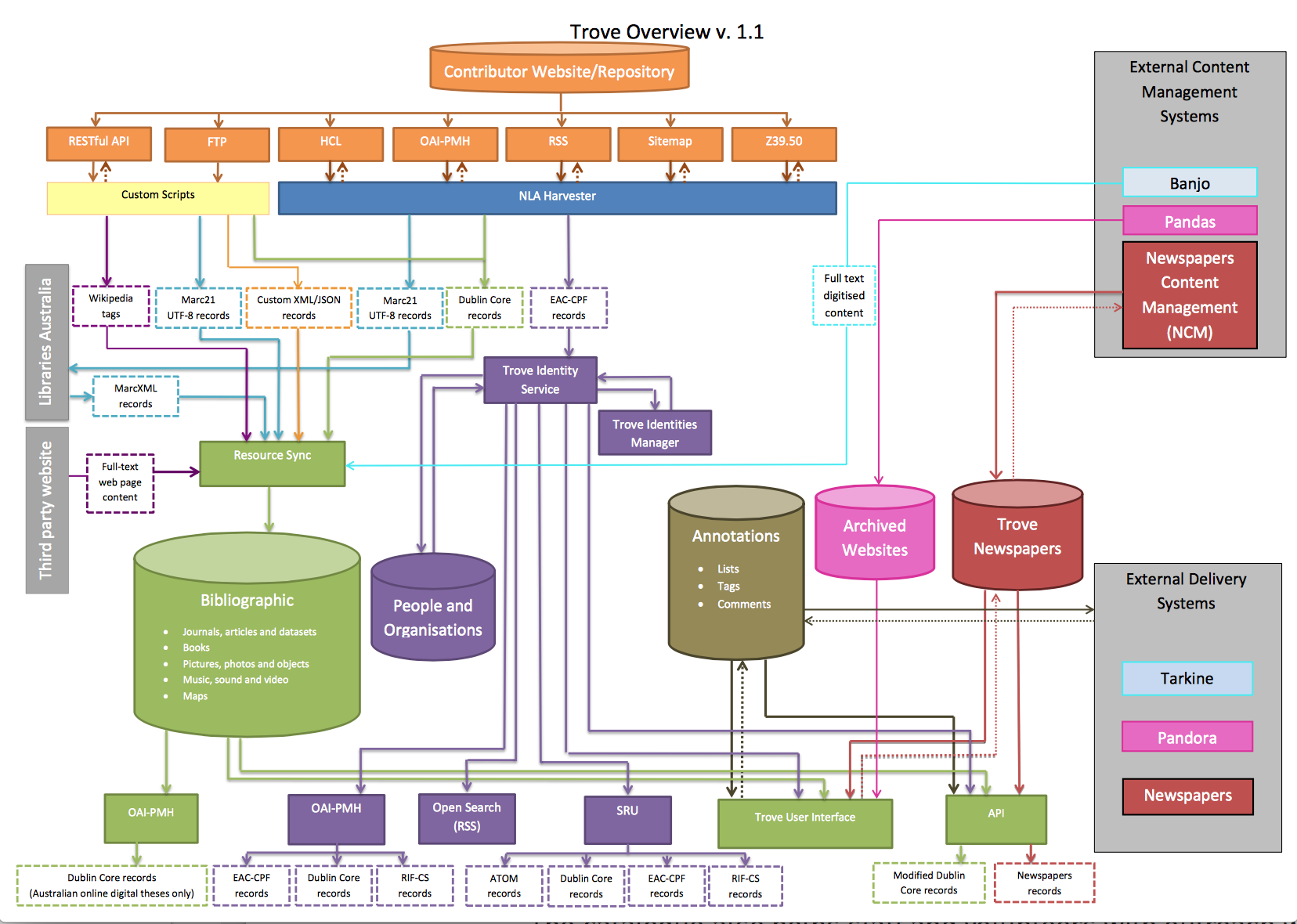

To the world Trove is a website, providing access to millions of resources, but if you look at how that information is managed it’s a much more complex (and messier!) picture.

EEEEEK!

So while we’ll be focusing on collection management systems it’s worth remembering that they will often exist within a complex ecosystem of datatabases, repositories, and indexes. And while we’d like to think that they’re all seamlessly interconnected, it’s possible that they won’t even talk to each other!

When is a CMS not a CMS? One of the most confusing things is that many cultural heritage institutions will have two different systems known by the same acronymn – CMS. A CMS can either be a Collection Management System, like the ones we’re going to look at today, or it can be a Content Management System. Content Management Systems, like Drupal or WordPress, are used to create and manage whole web sites. Beware!

Collection management systems

Here are a few well-known collection management systems. I’m including them here, not because I expect you to become an expert in them, or even remember their names. I simply want you to know that options exist. No matter what your software vendor, IT department, or senior management might say, there are a range of possibilities that should be considered before selecting a collection management system!

- Vernon – used by the National Gallery of Victoria.

- TMS – The Museum System – used by the Australian National Maritime Museum.

- EMu – now part of the bigger Axiell group of CMS products; used by the National Museum of Australia.

These systems are designed for larger institutions and have a price tag to match – although pricing information is hard to find as the systems are generally customised to the specific needs of institutions.

Over recent years, open source (ie free) alternatives have developed that match many, if not all, of the features of the proprietary systems. Of course, just because the code is free doesn’t mean there are no costs for implementation – once again considerable work can be involved in configuring, customising, and hosting the system. Open source options include:

- CollectiveAccess – used at the WA Museum

- CollectionSpace – mainly used by US university collections

- ArchivesSpace – used at the National Library of Australia

- AtoM (Access to Memory) – used at the ANU Archives

- Mukurtu – used by a number of Indigenous community groups

- Omeka – used by Deakin University

In between the large proprietary systems and the open source alternatives are a growing number of cloud-hosted services. These systems are generally less able to be customised, but they’re easier to set up and use. All the administration and data entry takes place on an external web server. Most of these services operate on a ‘freemium’ model offering a basic free account with the option to pay for greater capacity or more features. Some examples include:

- eHive – used by Canberra Museum and Gallery

- Victorian Collections – free to use for Victorian community groups

- Omeka.net – a hosted version of Omeka

- Mukurtu.net – a hosted version of Mukurtu

The library sector tends to be dominated by large companies such as ProQuest and the ExLibris suite, but there are open source alternatives like Koha.

So how do you choose between systems? There’s no easy answer but you might want to consider things like cost, ease of use, ease of access, compliance with standards, and availability of support.

Introducing Omeka

As I’ve mentioned we’re going to be using Omeka in our class project, so this is probably a good time to get an idea of how it works. As noted above, there’s a cloud-hosted version of Omeka – available at Omeka.net. There you can set up you’re own simple Omeka site for free!

Miriam Posner has written an easy-to-follow guide to creating your own Omeka site. I’d like you to follow Miriam’s instructions to create a site, add a minimum of 5 items, and add your items to a collection. The items can be anything you like – I’m not too worried about detail at this point, I just want you to get a feel for how Omeka works.

Portfolio alert! Once you’ve created your Omeka site, include a screenshot and the url in your portfolio, and share the url on Slack.