Why catalogue?

The Small Museums Cataloguing Manual describes two main reasons why it is important to catalogue a collection.

- Enriching cultural value

- Enhancing administration

By describing a collection you are capturing essential information about its meaning, value and context. This can provide the basis for further research, or support the development of exhibitions. In the case of archives, description also helps underpin the evidential value of the collection, embedding it within a set of organisational functions and relationships.

Descriptions enable discovery. As more and more collections become available online there are greater opportunities for collection items to be found and used. Connections can also be made across collections, further enriching their context.

Collections are also assets. A catalogue or descriptive system allows that asset to be managed efficiently by supporting decisions about where resources should be applied, or how priorities should be set.

Description is a form of intellectual control that allows us to grasp the meaning and signficance of collections. But it’s also a way of unleashing the cultural power of collections, freeing them to support new forms of use and interpretation.

The basics

While the basic purposes of description are much the same across the GLAM sector there are significant differences in the practice of description.

Library cataloguing, for example, is a very structured activity with broadly accepted standards for both the description of resources and the interchange of metadata. Descriptive practice in museums and archives is a little looser, reflecting the diversity and uniqueness of their collections.

But in general we’re trying to capture fundamental information that characterises and identifies the thing we’re cataloguing, such as:

- a name or title

- a brief description of the thing or its contents

- the physical format, including size and materials

- where and when it was created

- who created it

- any related items

- its current condition

We’ll also want to record some administrative information such as:

- a unique identifier for the item within the context of our collections

- a storage location

- any restrictions on access or use

Unique identifiers give you a way of referring to a specific item in your collection – not just a teacup, but a particular teacup. They are crucial in the effective management of a collection, and make it much easier for you to document relationships between items and share your collections with others. But they do require planning and maintenance. Sometimes you’ll find that items accrue multiple identifiers as institutions introduce new systems for the management of their collections – aaargh! Never underestimate the power and importance of a unique identifier!

The Small Museums Cataloguing Manual provides a handy worksheet that could be used in a small museum or community collection. Of course, much descriptive work is now done on computers using the sorts of systems we discused in the last module. But if you look closely, you’ll see that the type of information being captured is much the same. Another example worksheet is provided by Museums & Galleries NSW.

As we’ve noted, Omeka’s core fields are based on the Dublin Core standard. You can read more about why and how Dublin Core is used on the Omeka site. The original 15 elements defined by Dublin Core are:

- Title

- Subject

- Description

- Type

- Source

- Relation

- Coverage

- Creator

- Publisher

- Contributor

- Rights

- Date

- Format

- Identifier

- Language

Dublin Core is aimed at supporting the discovery of digital resources and is a bit fuzzy by design. Before starting any project, for example, you really need to agree on how you’re going to use elements like ‘Coverage’ – perhaps by identifying a standard list of placenames, or an agreed way of representing time periods? Remember why we have standards in the first place? There are also a series of extensions to Dublin Core that provide addition terms and controlled lists of values.

Portfolio alert! Below is a table listing most of the headings on the Small Museums Cataloguing Manual worksheet. By reading the manual, and the Dublin Core guidelines, I want you to create a ‘mapping’ that indicates how the Manual’s fields can be represented in Dublin Core. Include notes where necessary to indicate what sort of guidelines or limits (such as controlled vocabularies) might need to be applied. Some mappings will be obvious, but some might require a bit of creative re-purposing. If you think there’s no way of representing a field in Dublin Core, leave the column blank and explain your decision in a note. Copy the completed table into your portfolio.

| Cataloguing Manual heading | Dublin Core element | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Registration no. | ||

| Title | Title | Ok so this one’s pretty obvious. |

| Description | ||

| Keywords | ||

| Inscriptions and markings | ||

| Size | ||

| Maker’s details | ||

| When made | ||

| Where made | ||

| When used | ||

| Where used | ||

| Condition | ||

| Supplementary file | ||

| Restrictions |

Resources, processes, and contexts

CollectionSpace is a collection management system aimed at museums and special collections. Watch this short video to get an idea of how it works. You can also access the demo site and have a play around.

Create a New Object Screencast from CollectionSpace on Vimeo.

It looks a fair bit more complicated than Omeka, and there’s certainly a lot more fields than on the Small Museums worksheet. But let’s have a think about what’s actually being ‘managed’ in a collections management system.

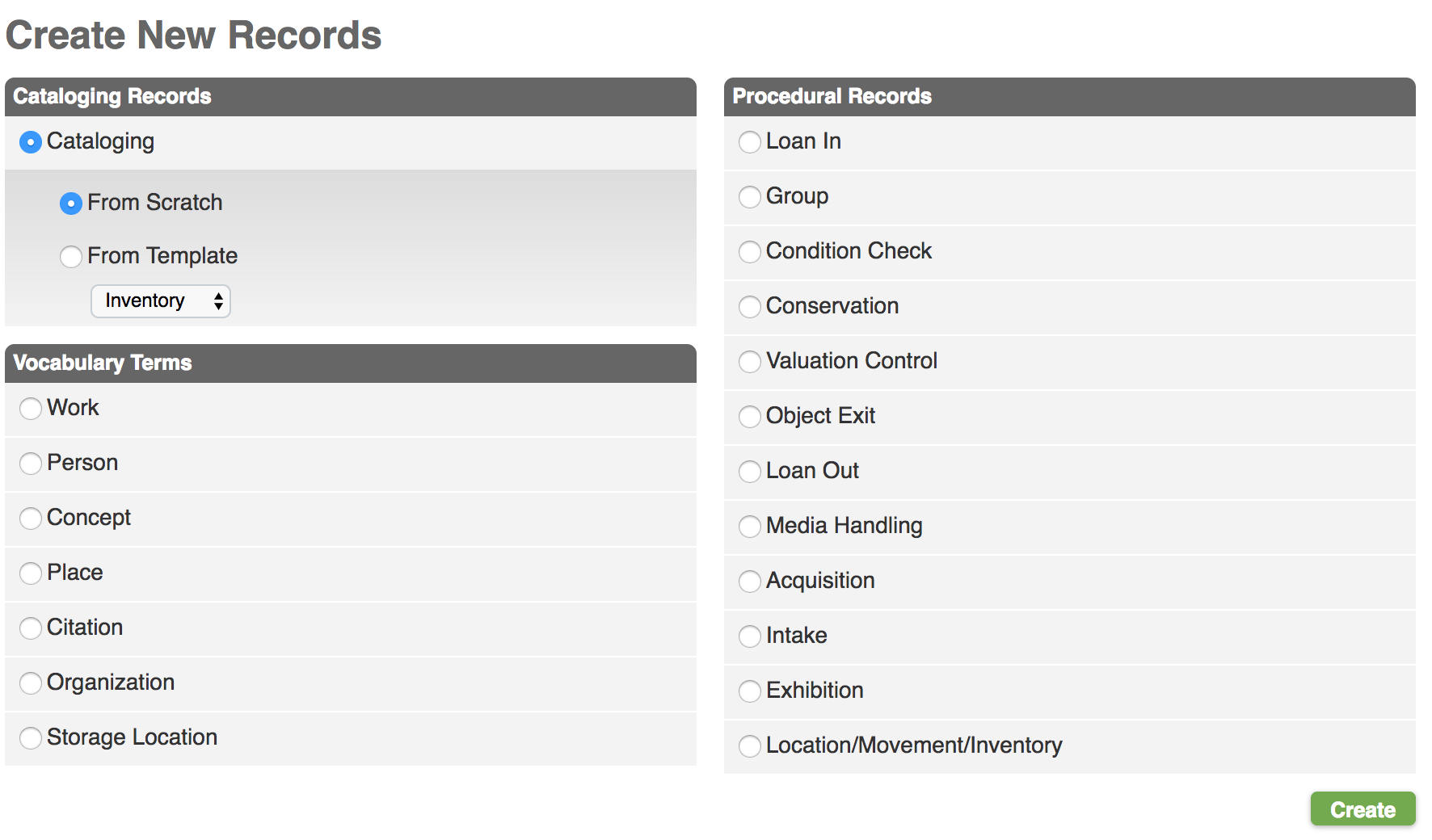

If you click on the ‘Create New’ tab in CollectionSpace you’re given the option to create records in three main categories – ‘Cataloguing Records’, ‘Vocabularly Terms’, and ‘Procedural Records’. The other systems have different names for these sorts of things, but what we’re basically dealing with are:

- Resources – the stuff of the collections (objects, documents, photographs)

- Contexts – the frameworks within which the collections are created, used, discovered, or understood (people, places, concepts)

- Events – the things that happen to collection items (loans, conservation, exhibitions)

Collection management systems are not just places for storing descriptions, they also embed those descriptions within a contextual framework that aids discovery and meaning. Objects don’t exist in isolation, they are linked to people, places, organisations and events. We’ll look more at how we represent and explore these contexts in the next module.

But the lives of resources also continue within their new institutional homes, so collection management systems also capture what happens to them after they’ve been ‘collected’. Look at types of ‘Procedural Records’ defined by CollectionSpace – you’ll see they all relate to the management of collections within an institution. Objects might be featured in an exhibition, digitised, or undergo conservation treatment – these events are also documented as part of the object’s history. Of course the use of these different types of records will depend very much on accepted practices within an organisation.

An important distinction between Omeka and fully-fledged collection management systems like CollectionSpace is the ability to capture this sort of administrative information.

Arrangement and description in archives

As we’ve noted in previous modules, the question of context is critical for archives in establishing a framework within the meaning and value of individual documents can be understood. The process of ‘arrangement and description’ is not just concerned with cataloguing individual items, but understanding the systems within which records are created. Indeed, records may be described at a variety of different levels depending on resources and need. You might begin by describing series, or groups, within the records. Based on what you learn through that process, you might decide to describe individual files, volumes, or documents, within selected series.

This video from the Public Record Office of Victoria provides a useful introduction to the practice of arrangement and description in a small archival collection.

There’s more information on the PROV’s ‘Documenting the collection’ page

Portfolio alert! The Documenting the collection page talks about the importance of ‘original order’ in archival description. In a few sentences, describe what you understand ‘original order’ to mean, and why you think it is important. Add this to your portfolio.

Documenting limits

We’ve mentioned the importance of description in making it easier to discover, access, and use collections. But description can also be important in understanding what shouldn’t be accessed, and what can’t be used.

Copyright is an obvious example. Documenting things like the date an item was created, and who created it, is critical in being able to make judgements about an item’s copyright status. The copyright status, in turn, will inform decisions about whether an item can digitised, reproduced, or shared.

But copyright is only one reason why access might need to be limited. Donors might place restrictions on the use of items. Access might also be controlled for cultural reasons.

Mukurtu is a collection management system that was developed for use by Indigenous communities and provides more fine-grained control over who has access to particular resources – why do you think this might be necessary? Read this introduction to Mukurtu and watch this video about creating cultural protocols in Mukurtu:

How to Create Cultural Protocols from mukurtu on Vimeo.

Portfolio alert! In your portfolio write a minimum of 200 words describing a situation where it might be necessary to control access to a collection. What types of metadata might help you document, understand, and manage these limits.