The contradictions of discovery

How do people find things in cultural heritage collections?

In the previous section we explored the importance of documenting context, both for preserving the value of collections, and for opening up new avenues for exploration.

BUT.

While both cultural heritage professionals and researchers understand the value of context, where do we go when we want to find something online?

Yep, Google. A 2013 study of Dutch scholars highlighted the ‘paradoxical attitude’ of scholars who, while emphasising the important of provenance and context to research, nonetheless relied heavily on Google to discover resources.

What’s wrong with that? Nothing – as long as we understand the biases and limitations of search engines like Google. As the study notes, search engines ‘do not simply retrieve information, but co-produce information by ranking and indicating the importance of information’. The results we see when we search for something in a search box are the result of complex ranking algorithms that try to predict what will be most relevant.

Most relevant to who? Your results might not be the same as mine. Search results are increasingly personalised based on things like your location and web browsing activity. The exact formulae used for results ranking are largely unknown. Search engine algorithms tend to be ‘black boxes’ – we use them, but we don’t really understand how they work.

Try the following search in Google site:trove.nla.gov.au. The site: modifier is a handy little trick that tells Google to limit results to a particular site or domain – in this case Trove. How many results does Google find? When I tried Google thought there were ‘About 1,900,000 results’. But you might get a different estimate – it can vary between computers and users. Don’t be tricked into thinking that Google tells the ‘truth’.

Hopefully you will remember that Trove holds considerably more than 1,900,000 resources (try half a billion). So what’s going on? As well as the mysteries of results ranking, and the inaccuracy of its estimates, Google only indexes what Google indexes. While Search Engine Optimisation is now a business in itself, you simply can’t make Google index all your stuff. All you can do is to try and make your online content as Google-able as possible. And hope.

Discovery happens elsewhere

Back in 2007, the library thinker Lorcan Dempsey coined the phrase ‘discovery happens elsewhere’ to encourage libraries to think about how they were exposing their metadata to the world. It’s not enough to have your own shiny web interface because, like it or not, a large proportion of your users will prefer to use Google.

Ok, so I just said that we really don’t have any control over what Google indexes and displays. That’s true, but there are things we can do to make collections more discoverable on the open web.

-

Use persistent urls. If you want people to find your stuff DON’T CHANGE YOUR URLS! It seems sort of common sense, but it’s amazing the number of times institutions install new systems or redesign their sites and break all their links. Have a look at ‘Cool URIs don’t change’ for the basic arguments. And if you don’t think this is a problem, have a look at the Wikipedia article on Link Rot.

-

Expose links to your collection items. If the only access to your collection is through a search box, Google can’t index your collection. You need to provide ways for search engines (and human beings) to browse your collection – to follow links that lead through to individual items. You can also use things like sitemaps and RSS feeds to publish lists of links in a form that machines can understand.

-

Include metadata. Remember our discussion about Linked Open Data and Schema.org? Schema.org was developed by search engines to aid discovery. You can use it to share basic information about collection items – like their title and creator – with search engines or other data aggregators. At the very least, you can use ‘meta’ tags to provide basic page-level data. Here’s an interesting blog post about using Schema.org and Google to provide library search services.

There are more Google-specific strategies you can implement, but the three points above are fundamental to web resource discovery in all its forms.

Sharing collections online

But as well as optimising your own collection site for improved discovery, you can push your collections out into the wider world. Set your collections free!

For example, cultural institutions often share their photographic collections using platforms such as Flickr. In fact, there’s a whole special section called the Flickr Commons where cultural organisations can share public domain images. (What’s public domain? We’ll talk about that below…) By sharing images on Flickr, organisations open their collections to new audiences. Often the images will be viewed many more times on Flickr than they will on the institution’s own site. Some small organisations without their own web presence have used Flickr as their main collection site. Have a browse of the Commons’ list of ‘participating organisations’ – how many Australian organisations can you find? How many images do they share on Flickr?

There are doubts nowadays about the future of Flickr, but there are plenty of other ways to share collections. The State Library of Queensland, for example, donated 50,000 images to the Wikimedia Commons. Indeed, GLAM organisations all over the world are collaborating with the Wikimedia community in a number of different ways to highlight the contents of our cultural collections. See the GLAM-Wiki site for more information and ideas.

One great example of the possibilities is provided by the British Library which, in 2013, released over 1 million images on Flickr. The images came from scanned books from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries and were shared without any restrictions for people to use, research and play. This generated enormous excitement and large amounts of web traffic on Flickr. The Wikimedia community started adding the images to the Wikimedia Commons as well, but they also developed a series of indexes to make it easier for for people to explore the collection. Here’s the Australian images.

The images have even been used in an art installation at the Burning Man festival in Nevada.

Life on the outside

Why should you expect people to come to your web site to find and use collections? Why not push collections out into the spaces where people already congregate. Social media provides another way of making collections discoverable.

As well as being on Flickr and the Wikimedia Commons, the British Library’s million images are also shared on Tumblr and Twitter. Computer scripts (usually called bots) choose and post random images. The British Library’s @MechCuratorBot is just one example of a growing army of Twitter bots sharing random collection items.

16 Jun 1928: '"WEST AUSTRALIAN" v. "SUNDAY TIMES."' https://t.co/aFgTty3NrE // re ABC: https://t.co/danO3Qo3Ep

— TroveNewsBot (@TroveNewsBot) September 30, 2016

I’ve made a few myself! @TroveNewsBot shares newspaper articles from Trove, while @TroveBot does the for the rest of Trove’s resources. But these bots do more than just post random stuff. Tweet keywords at them and they’ll search Trove, tweeting back the most relevant result. Yes, you can search Trove without ever leaving Twitter! There are more search options on the GitHub pages for @TroveNewsBot and @TroveBot. Here’s a few things you can try:

- Tweet #luckydip at either bot for a random resource.

- Tweet a url and the hashtag #keywords to find resources relating to a web page.

But social media can hold dangers for cultural heritage collections. Have you ever come across the @HistoryInPics (or some similar) Twitter feed? It’s an account that tweets out historical images. Sounds good huh? Hmmm, perhaps you should read Sarah Werner’s post ‘It’s history not a viral feed’.

If you want people to share your collections then make it easy for them to do it properly:

-

Use persistent urls I know I’ve mentioned it already, but IT’S SO IMPORTANT I can’t help but mention it at every opportunity. Some collection sites still don’t have individual urls for items. Seriously. Some collection urls break when you try to share them (looking at you RecordSearch). If we want people to attribute the source of collection items we need to give them urls that work!

-

Provide example citations. If you want people to properly attribute a collection item, show them how. Provide an automatically generated citation that can just copy and paste into their post.

-

Include metadata. This one’s worth repeating as well. Services like Twitter and Facebook define specific guidelines for publishing item metadata so that it can be easily retrieved and displayed when someone shares that item. It’s this metadata that’s used to create things like Twitter cards.

-

Tell people how they can use your collection. Persistent urls and the rest are not much good if the licensing information you provide makes people frightened to share your collection. If something is out-of-copyright, then say so. If it’s openly licensed, include details. Blanket statements about checking with the institution before use do not encourage sharing or creativity.

Sarah Werner provides some important tips in her talk on how to destroy special collections with social media.

Beyond the silos of the LAMs

A 2008 study called ‘Beyond the silos of the LAMs’ explored ways that libraries, archives and museums could collaborate to improve discovery. I mention it here mainly because it has the best title of all time.

A lot has happened since 2008. In particular a number of large-scale aggregation services have been developed to pull together collection items from across the GLAM sector. There’s:

- Trove (of course, aggregating content from Australia)

- DigitalNZ (New Zealand)

- DPLA (Digital Public Library of America)

- Europeana (many European countries)

Each of these services has a different emphasis and use different technologies, but they all aim to make cultural collections easier to find and use. They do this by:

- Harvesting and indexing collection item metadata from lots of different GLAMs (and other organisations). This is the aggregation part of things – it creates a big centralised database of stuff.

- Making all this stuff easily available for discovery and reuse.

Discovery and reuse? Each of these services provides a familiar-looking search portal – just type in your queries and off you go. But, more importantly, each of these services makes their aggregated data available in a form that computers can understand via an API (Application Programming Interface). As we’ll see below, this means that anybody can build new tools and interfaces that open up cultural collections in innovative and interesting ways. Aggregation brings metadata together. APIs send it back out into the world. Together these technologies enable new forms of discovery.

Interfaces

We’ve already had a bit of a look at online collections – or at least at the basics of search and browse. Omeka itself provides a good example of a no frills interface, providing the basic navigation that we would expect of a collection interface. But what else is possible?

Let’s have a look at some recent collection interfaces from museums around the world. Spend some time exploring the features of these difference interfaces. Try searching for something you’re interested in. Then try browsing without any particular subject in mind.

While you’re exploring, think about things like:

- What do you find useful, interesting, or frustrating?

- Is it easy to find your way around and understand what to do?

- Is the amount of information presented adequate?

- Are there interesting connections to explore?

- Did you come across something unexpected?

- Was there something you wanted to find but couldn’t?

- Would you go back?

All of these interfaces offer something more than your standard search box. In different ways they all provide pathways for exploration – you can look around the collections without first knowing what you’re looking for!

Mitchell Whitelaw calls these ‘generous interfaces’:

‘A more generous interface would do more to represent the scale and richness of its collection… Instead of demanding a query it would offer multiple ways in, and support exploration as well as the focused enquiry where search excels. In revealing the complexity of digital collections, a generous interface would also enrich interpretation by revealing relationships and structures within a collection.’

Generous interfaces invite you in. Have a look at:

What do you think? Do these encourage you to explore the collections?

These sort of interfaces cross the boundary into data visualisation – they don’t just provide pathways into the collections, they enable you to see them in very different ways. They make use of existing metadata to develop new representations of the collections that offer users new points of access and understanding.

The Loom project at the State Library of NSW presents a number of different ways of looking at their collections. Try out the ‘Loose leaf’ and ‘Atlas’ views – what can you find?

Portfolio alert! Read Mitchell Whitelaw’s article and explore the various collection interfaces linked above. In a minimum of 100 words, describe which of these collection interfaces you think best invite open-ended exploration and discovery. Explain your choice.

Reusing collection data

One of the interesting things about these sorts of innovative, exploratory interfaces is that they’re often not created by the institution that holds the collection. As more and more collection data is shared, either as data dumps or APIs, creative coders around the world are finding new things to do with cultural collections.

Headline Roulette is a simple game that I made using the Trove API. It presents you with a random newspaper article and you have to guess the year in which it was published – it’s harder than it sounds!

Note that whether you lose or win, you get a link through to the original article to explore further. It’s a type of discovery interface. You can also create your own customised version of Headline Roulette.

All the aggregators have galleries of applications that people have created using their APIs – have a look around and see if you can find something interesting.

In particular you might like to try:

- Culture Collage – browse images from multiple sources

- Explore Europeana by colour

- Succession

Europeana has made strong argument for the importance of digital access to cultural heritage collections. It’s not just about access, they argue, but the role of digital cultural heritage in supporting innovation. Have a look at the Europeana Strategy 2015-20 – for a strategy document it’s remarkably readable! If you’re ever wondering why we bother, why documenting and sharing cultural collections is important, this is a good place to start.

Research

But digital collections don’t just support new interfaces or artworks, they enable new types of research. We can ask different types of questions.

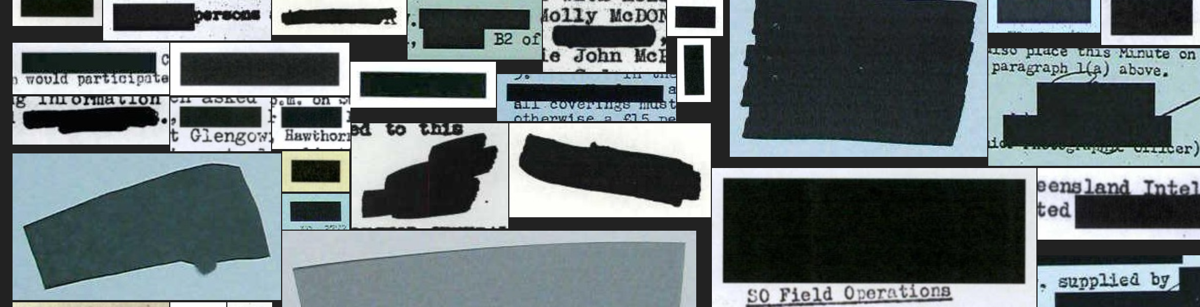

Some of you have heard about my ongoing battles with ASIO files in the National Archives of Australia. I’ve downloaded many thousands of digitised pages and extracted information about redactions – the bits that are blacked out for security or other reasons. I’ve also created my own interface that allows you to explore the redactions (and even some unexpected redaction art). I’m going to use the data I’ve collected about redactions to try and understand the way ASIO collected and stored information. None of this would have been possible if the National Archives hadn’t digitised the files and made metadata available through their online database.

There are exciting opportunities for finding new patterns and perspectives within existing collections. Viral Texts is a project that is using digitised newspapers to shine new light on the processes by which information was disseminated in the 19th century. They’re using software originally developed for genetics research to track patterns in text. Did you think the ‘listicle’ was a product of the Internet – the Viral Texts project has shown that lists of ‘interesting facts’ were very commonly shared by 19th century newspapers.

If you’re interested in new possibilities for art history have a look at Matthew Lincoln’s work drawing on a number of digital collections.

The future?

Throughout this unit we’ve seen examples of where technology is heading – new tools and technologies will help us to look at collections differently, to share them more effectively, to create new opportunities for learning and research. But at the same time, we’ve seen how important it is to get the basics right. Interfaces come and go, but good metadata lasts forever (or for a lot longer anyway!). Questions about value and significance will still be important in grappling with the complexities of digital collections.

Portfolio alert! Read Europeana’s Strategic Plan and explore the various articles and examples linked on this page and think about how we will find and explore cultural heritage collections in the future. Europeana’s slogan is ‘we transform the world with culture’, in a minimum of 200 words explain how making cultural heritage collections available online can ‘transform the world’. What changes and why?