7. Understanding search#

Learn about some of the limits, complexities, and challenges of using search in Trove.

7.1. The limits of search#

Search is such a fundamental part of our online lives, we don’t really think about it much. We just type words into the box, click enter, and start wading through the results. But search indexes have biases, they embed politics, they make assumptions about who we are and what we want. This is as true of Trove as any search tool.

In particular, search interfaces like Trove are not good at communicating their own limits. They tell us what they’ve found, but not what is findable. This has important implications for researchers trying to interpret their search results. What does it mean if your Trove query returns nothing? Have the relevant resources been preserved, catalogued, digitised, indexed? Is there an issue with copyright? Are you searching the full text or just metadata? Is the metadata complete and consistent?

On the other hand, search interfaces can sometimes be too helpful, returning results of limited relevance just in case they might be of interest. Trove builds a certain amount of fuzziness into its results for this reason. But if you’re using Trove to assemble and analyse large-scale datasets, you need to understand and control this fuzziness – to understand the limits of your dataset.

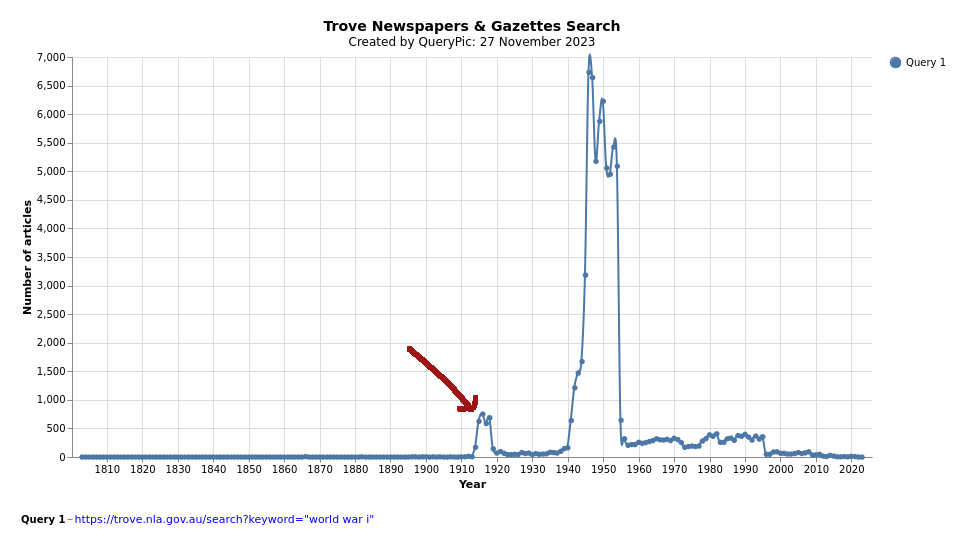

Trove’s digitised newspapers can help you find and track changes in language and terminology. For example, at some point Australians started referring to ‘the Great War’ as the ‘World War I’, but when? You can explore this question by using QueryPic to visualise newspaper searches for ‘the Great War’, ‘World War I’, and ‘World War II’.

Fig. 7.1 Number of digitised newspaper articles matched by the queries ‘the great war’, ‘world war i’, and ‘world war ii’.#

Not surprisingly, it seems that the shift in language occurred in the 1940s, but if you look closely at the ‘world war i’ results you notice something odd – there’s a noticeable peak from 1914 to 1919. But this is not because people were envisaging that the current war would be one in a series. It’s because Trove users have been adding the tag ‘World War I’ to articles from the period, and Trove searches user tags and comments by default.

Fig. 7.2 Number of digitised newspaper articles matched by the queries ‘world war i’.#

Trove’s default behaviour helps people find relevant articles, leveraging the knowledge of Trove users. But it also pollutes the data, mixing up the provenance of keyword matches. But the main problem is that it’s just not obvious that this is happening. Trove does little to alert you to the scope of its searches. Nor is there an obvious workaround. You can exclude matches in tags and comments by adding the text: prefix to your keywords, but this also switches off word stemming, so the results are not exactly the same.

If you’re going to use Trove data in your research, you need to think beyond the search box, to question your own assumptions, and think critically about the systems that deliver the data to you.

7.2. Search is a research method#

If you’re working in a physical archive you don’t expect to just submit a query to the person on the desk and have every relevant record delivered to you. You have to learn about the provenance of the records and the way they’re arranged and described. It takes time, but it’s a key part of the research process.

You should treat Trove the same way. Each search is an opportunity to learn a little more about the way Trove works. If you don’t find what you’re looking for, consult the documentation and experiment with alternative queries. Think about what works and what doesn’t. It’s an iterative process.

Understand the technical context — How does it work? Consult the documentation (and this Guide) to understand your options.

Be creative and strategic — Solve your puzzle by experimenting and looking for clues in the results.

Stay critical — Always assume that Trove isn’t telling you everything.

With so many rich cultural heritage collections now available online, constructing and interpreting search queries has become an important research method for HASS researchers.