Working at scale

This unit is about thinking through the possibilities and implications of digital technologies in the cultural heritage sector.

As a historian, I’m always suspicious when someone starts talking about ‘revolutions’, particularly with regard to technology. Yes there’s change, but there’s also continuity. For example, we have to remain critical of historical sources, whether or not they’re delivered in digital form. Simply because they’re conveniently delivered to our screens doesn’t make digitised documents more truthful or more reliable. We still have to ask questions.

What sort of questions might we ask? The digital historian, Adam Crymble, gives a glimpse of some possibilities in this two minute version of his PhD thesis:

Digital tools provide a way of dealing with the large volume of material that is now becoming available in digital form – of grappling with the challenges of abundance.

Seeing differently with QueryPic

One example of this is a simple tool I created called QueryPic. QueryPic visualises searches in Trove’s newspapers zone. What happens when you search the more than 200 million articles available on Trove and get back 10,000 matching results, or 100,000 – how do you make sense of that? Instead of just providing a list of search results, QueryPic shows you the number of articles each year that match your query.

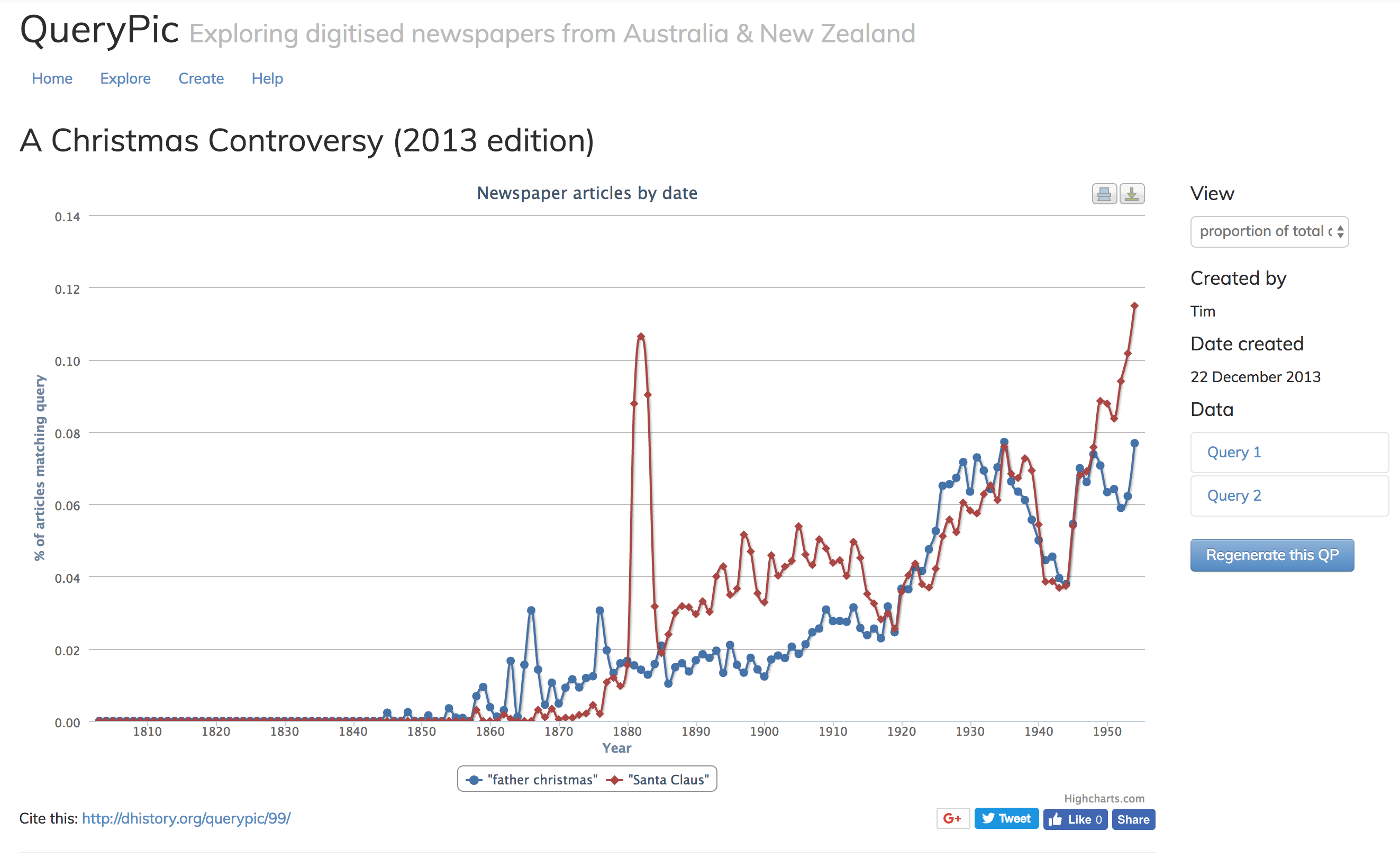

Just in case you’ve ever wondered what we should call the guy in the red suit who turns up at Christmas time, I’ve created a QueryPic for you – have a look at A Christmas Controversy.

This QueryPic displays the results of two searches – one for ‘Santa Claus’ and the other for ‘Father Christmas’. Drawing on that huge body of digitised text from 1803 to 1954, we can explore changes in language over time, or the impact of specific events.

Note that by default QueryPic shows the number of matching articles as a proportion of the total number of articles published that year. This makes it easier to see results in the earlier decades, when fewer newspapers were published. You can easily change this – just choose ‘number of articles’ from the dropdown box under ‘View’. You’ll then see the raw number of matches.

What do you notice about the battle between Santa Claus and Father Christmas? Which name was most commonly used in the 19th century? It seems that Father Christmas became more common in the First World War period. Why might that be?

Be careful. QueryPic provides more questions than answers. It’s a way of seeing those millions of newspaper articles differently, but we still have to think about what these visualisations are telling us. They’re sketches, not arguments.

You’re probably wondering what happened to Santa Claus in 1882. Using QueryPic you can drill down to explore what’s going on at any point.

Click on ‘Santa Claus’ peak in 1882. When you click on a point, QueryPic fires off a query to Trove, asking for the first 20 results from that year. Hopefully, you should soon see a list of the results appear at the bottom of the page. (Sometimes the request fails and you have to try again.)

Have a look at the results – notice anything interesting? Without actually reading any of the articles you should be able to pick up enough clues to make an educated guess about why ‘Santa Claus’ was mentioned so often in 1882. [Hover for answer]

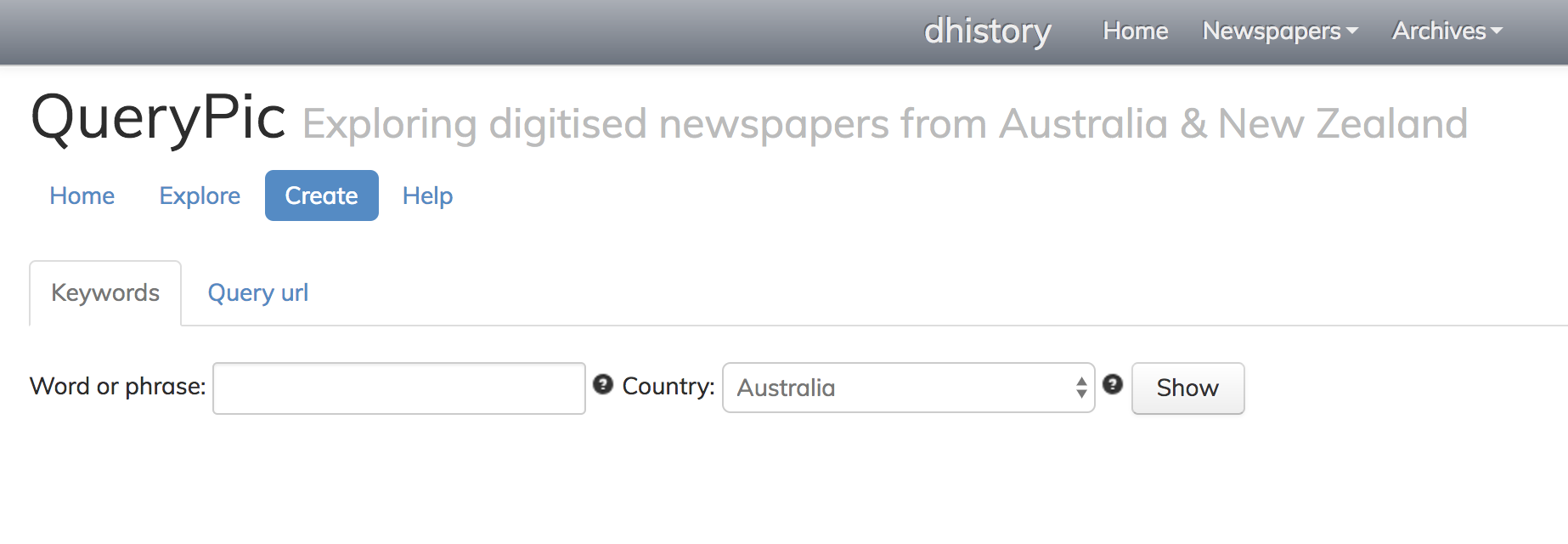

It’s easy to create your own QueryPics – let’s do it now!

- Click on the Create tab

- Think of a couple of words or phrases you’d like to compare. You could examine changes in spelling or terminology – ‘aeroplane’ vs ‘airplane’. You could track the evolution of technology – ‘steam engine’, ‘horse’, ‘motor’. You might want to try your searches in Trove first just to see what sort of results you get.

- Enter the first word or phrase (you need to put double quotes around phrases) in the box. Click the Show button.

- Repeat with your next word or phrase.

- Once you’ve finished click the big blue Save button and enter some details.

- Once it’s saved, your QueryPic will have its very own persistent url that you can share. Copy it and share it on Slack.

- If you have any problems, consult the excellent help page. You can also explore QueryPics that others have created.

Portfolio alert! In your portfolio save the url to your QueryPic. In a few sentences describe the searches you used and results you obtained. Did you come across anything surprising?

Go international! You might have noticed there’s a dropdown box on the ‘Create’ page where you can choose between Australia and New Zealand. This lets you compare searches in Trove and NZ’s Papers Past. Give it a go.

Tools like QueryPic help us to see things differently. But we have to be prepared to ask questions about the assumptions they make, about the biases that are built in to their algorithms. Our ability to work with vast quantities of digital data has changed, but the need to be critical remains.

Digital possibilities and problems

Last year I gave a keynote presentation to the Professional Historians Association conference in Melbourne. It provides a fairly broad introduction to the ways we can use digital technologies with cultural heritage collections. Please watch it. You’ll notice some familiar (and unfamiliar) examples…

The full text is available on my blog, and you can also follow along with the slides.

Stephen Robertson explores some similar questions in The Differences between Digital Humanities and Digital History.

Both my talk and Stephen’s chapter include links to a variety of digital projects. Take some time to explore them and get a sense of the sorts of things that are possible. Is there a particular approach that interests you – digital mapping, visualisation, text analysis, computer vision?

Portfolio alert! Pick one of the projects mentioned by me or Stephen and write a brief (200 word minimum) review. What interests you about the project? What does it allow us to do or see that we couldn’t before?

Paths and sandboxes

As I mentioned in the video, a couple of years ago I started to collate information about websites that included links back to digitised newspaper articles on Trove. I wanted to understand more about the contexts in which the newspapers were being used and cited. The diversity of subjects and sites was astonishing, and sometimes disturbing.

You can browse for yourself at Trove Traces. Though, be warned, not all of it is pleasant.

Have a look under the ‘Analysis’ menu where you’ll find a list of Top pages – these are the sites with the most links to Trove. You’ll see there’s a huge amount of work being done. In the video I highlighted KnowThatProperty.com which provides potted histories of houses around Sydney, largely drawn from Trove. But that’s just one example. Browsing through Trave Traces really makes you think about what happens when digital heritage resources are made available online. People aren’t simply consuming these resources, they’re creating with them. They’re out there pursuing their passions – finding, collecting, and using stuff.

An important concept to keep in mind is the ‘long tail’, first identified by Chris Anderson. The idea of the ‘long tail’ emerged from online retailing and the recognition that stores no longer had to try and guess what their shoppers would like. They could just make everything available online and let shoppers find what they were interested in. Instead of focusing on a single mass market, they could service an infinite number of niche markets.

Think about how this might apply to cultural heritage collections. Museums only ever have a tiny fraction of their collections on exhibition, but if they could make their complete collection available online they open up new opportunities for people to discover their own interests, create their own exhibitions.

My standard example of this is a guy who, at last count, has created over 200 Trove lists about lawn mowers. He’s mining the newspapers for advertisements and creating a list for each make of mower. People always laugh when I talk about this, but I think its wonderful that you can create opportunities like this for people to pursue their passions. And, like KnowYourProperty.com, this sort of searching and organising of sources is the hard graft of history.

Game designers sometimes talk about the difference between ‘paths’ and ‘sandboxes’. Paths guide you along a particular journey, while sandboxes encourage open-ended exploration. Minecraft is the obvious example of a sandbox game. One writer has described this as the difference between ‘exhaustibles’ and ‘possibility engines’.

I love the idea of using cultural heritage collections to create possibility engines. Not sites, not interfaces, or even experiences – but jumping off points into a rich new world of discovery, creation, and collaboration. It’s not about inviting the public in, it’s about giving them room and perhaps a bit of inspiration.

Oh and two more Trove community examples…

Meet Elegant Elephant. This is a knitting pattern publishing in the Women’s Weekly in the 1950s. No-one would probably know about him except for the fact that the pattern was found and shared on the knitting site Ravelry. He has now been made at least 54 times and the pattern regularly features amongst the most popular articles on Trove.

Or what about the guy who has been finding old, copyright-free, Australian sheet music, recording the music using his computer, and linking the recordings to the original entries in Trove. Now you can not only see the sheet music, you can hear it performed. There’s more about him on the Trove blog.

The publics of digital heritage

In The public is dead, long live the public Sheila Brennan argues that just because something is online doesn’t mean that it’s public. The design of a digital project has to begin with an understanding of who your ‘public’ actually is and how you can best engage with them.

We’ve already talked a bit about crowdsourcing in the context of our class project – crowdsourcing projects invite the public to help with particular tasks relating to research or the description of collections. There’s a great summary here of the characteristics of crowdsourcing projects in the cultural heritage sector. The correction of OCRd text in Trove’s newspapers is often held up as a sucessful crowdsourcing project. What’s On the Menu from the New York Public Library is another well-known, and very successful, example.

But crowdsourcing projects raise a lot of interesting and important questions about the relationship between institutions and the public. Is crowdsourcing just cheap labour, or is it an opportunity for the public to be actively involved in the work of cultural heritage organisations? Lori Byrd Phillips examines the idea of ‘open authority’ and how digital platforms can allow power to be shared differently between institutions and their publics.

Trevor Owens discusses what motivates people to become involved in crowdsourcing projects and he talks about providing ‘scaffolding’ rather than just assigning people tasks. Scaffolding, he argues, lets ‘people offer up their time and energy to work that they find meaningful’.

As we develop our own project, I think it’s important to keep in mind the question of how we create, or allow others to create, meaningful connections to the past. People will always surprise us.

If you haven’t already visit Zooniverse – the home of many of the most innovative crowdsourcing projects. Originally focused on ‘citizen science’, Zooniverse is increasingly getting involved in the cultural heritage sector. What arts, humanities, and cultural heritage projects can you find? Sign up and have a go!

The Atlas of Living Australia also has a digital volunteer site where you can work on a variety of Australian citizen science projects, including the transcription of historical expedition journals.

Portfolio alert! I want you to choose one crowdsourcing project and invest some time in it – a minimum of an hour. Reflecting on the issues, questions and readings above, I want you to write a short 500 word (not including Harvard-style references if required) essay on the experience. What made you interested? What did you enjoy? What did you find frustrating? What do you now think about questions of motivation, meaning, and authority?

The politics of digital heritage

As I said, I’m a hacker. I want to use digital tools and technologies to make a difference. I think it’s important for us to reflect on why this sort of work matters. Here are three talks which all address the ‘why’ question, though in different ways.

- Thomas Padilla, Conditions of Possibility

- Miriam Posner, What’s Next: The Radical, Unrealized Potential of Digital Humanities

- Tim Sherratt, Unremembering the forgotten

A video of Thomas Padilla’s keynote is below, however, it covers the the whole day(!), so you’ll need to skip ahead to the 7:35 mark to catch the start of Thomas’s talk.

Think about the three themes in Thomas’s talk and how they might relate to the sort of tools and technologies we’ve been exploring:

- Ethics – what are our responsibilities?

- Empowerment – how can we share what we know?

- Agency – who has the power and why?

Portfolio alert! How might issues of ethics, empowerment, and agency arise in our own class project? I’d like you to write a minimum of 200 words on how we might address these issues as we develop our project. What do we need to be careful of, and why?