#redactionart

Commonwealth government files more than 20 years old are supposed to be made available to the public. However, before they’re released they go through a process known as ‘access examination’. The contents of the files are checked against a list of exemptions – things like privacy and national security. Depending on the results of the access examination process, files can be completely withheld from public access or opened ‘with exception’. In the latter case, whole pages can be removed, or individual words or phrases can be blacked out – these are called redactions.

I decided to try and find redactions in publicly available ASIO files held by the National Archives of Australia. Extended movie-like montage follows…

And then there’s the sequel where #redactionart escapes from my computer and unleashes havoc upon the world…

And of course there’s the trailer…

The Redaction Zoo from Tim Sherratt on Vimeo.

Images as data

I thought I’d share my redaction art discoveries today because they’re an example of how digital tools and techniques can lead you in all sorts of unexpected directions; but more importantly they also show how data can be used to generate new data. In this case I started with a set of digitised page images from ASIO files held by the National Archives of Australia. From those images I extracted the coordinates of redactions and created a new dataset containing 239,571 individual redactions that will enable me to look for patterns in redaction over time. But in the process of compiling that dataset I discovered redaction art, and traced the outlines of some of the creatures to create a new collection of SVG files. Those SVG files have in turn been converted into 3D models (and cookie cutters).

Of course, we’re currently doing the same sort of thing with our transcription project. We’re starting off with a collection of images of documents, and we’re extracting data from them. In this case humans are doing most of the work rather than machines, but the end result will be similar – new datasets for research, exploration and analysis. Transcription projects like ours turn human-readable data (images) into machine-readable data.

Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is another familiar example of this process – computers turn images into text. Current OCR software is pretty fussy, and will generate garbage if the imaged texts are not good quality. That’s why Trove asks users to help them clean the OCR transcriptions of digitised newspaper articles. But in recent years there have been significant advances in computer-aided transcription of handwriting.

What other sorts of data might you extract from images? A few years ago the Cooper Hewitt Museum developed a browse by colour interface to their collection. They describe the process of extra color data from each of the images in their collection and matching them against specified colour palettes. ImagePlot is a software tool developed by media researchers in the US that visualises relationships between images based on derived properties such as brightness, saturation and hue. Here’s an of the paintings of Piet Mondrian plotted over time. The closer together the images, the more similar they are in terms of the derived image data. As Mondrian’s work become increasingly abstract, the distances between them increase.

Seeing like a computer

We can also look for objects, shapes, or ‘things’ in images. This is a technology known as ‘computer vision’, and it’s everywhere these days – from automated image tagging on social media sites, to facial recognition at airports.

My redaction art research is a very simple example of how you can use computer vision technologies to extract data from images. There’s no pre-built tools for finding redactions (at least not that I know of), so I had to code my own. However, there is a very widely-used library of code called OpenCV that meets most computer vision needs.

I’ll save you all the coding details, but I did want to walk you through the process. If you’ve used image editing tools like Photoshop, some of these steps might be familiar.

- I removed the colour from the image (converted to grayscale).

- I blurred the image slightly to remove some of the background noise, but I used a technique that is supposed to maintain sharp edges.

- I applied thresholding to reduce the image to black and white.

- I found all the black bits in the image.

- I traced the contours of all the black bits to find their shape.

- I looped through all the contours rejecting any that seemed too large, too small, or too close to the edge of the image.

- I found the centres of the contours that were left and checked that a 10px x 10px sample from the centre was all black.

- I then grabbed a rectangular box around each of the remaining contours and saved it as a new image.

This is almost certainly not the best or most efficient way of finding redactions. I developed my script by trial and error against a set of test images. Even so, there’s so much variation amongst the source images that I’ve ended up with 15-20% of false positives. I’d like to find a way to reduce that.

You might be thinking that it seems like a lot of work to find a little (or not so little) black blob. And it is. One of the things your constantly reminded of when working with computer vision applications is how good humans are at recognising patterns. It’s a lot harder for computers!

Finding faces

People are particularly good at recognising faces. In fact, we’re so good at it that we tend to ‘see’ faces all over the place – this is called pareidolia. Have a look at the photos shared by @FacesPics on Twitter – do you see the faces?

Jazz hands bridge is happy! pic.twitter.com/D5hnkI3IPA

— Faces in Things (@FacesPics) September 29, 2016

Faces don’t matter much to computers, so they’re not hardwired to recognise them in the way we are. However, facial detection is a very common computer vision task. So how do you do it?

First of all we need to distinguish between ‘facial detection’ and ‘facial recognition’. Facial detection is just finding a face in an image – it’s what happens when your camera draws a box around faces as you’re taking a picture.

Facial recognition means taking an image of a face and then matching it against a database of previously identified faces – it aims to identify the owner of a face. We see facial recognition all the time on TV crime shows, though in the real world it’s rather more complicated. Facial recognition is much harder than facial detection – though the computers are learning fast!

Facial detection is one example of a broader category of computer vision tasks called object detection – the ability to identify particular things in a image. The objects you’re looking for might be faces, dogs, or bananas, the approach is basically the same. First you use a selected set of images to create a model of the thing you’re looking for. Then you can use this model to detect instances of that thing in a new set of images. It’s sometimes referred to as machine learning because you’re training the computer to ‘see’ the thing you’re interested in.

What sort of uses might this technology have in the cultural heritage sector?

So to find bananas you’d train your machine with two sets of images – one with bananas, and one without. It would gradually learn to spot the features that define a banana. But what makes a face? The models included with OpenCV are pretty basic and really just look for bands of contrast where the eyes nose and mouth should be. To demonstrate this I tested a facial detection script on a set of simplified faces. This, for example, was detected as a face:

This video shows how a basic face detection model or classifier analyses a new image. It moves a window across the image looking for matching features. If enough features are detected it saves the window as a possible match. If a number of these marked windows overlap, it’s likely to have found a face.

OpenCV Face Detection: Visualized from Adam Harvey on Vimeo.

What’s interesting is the way that a complex task – recognising a face – is broken down into a large series of very simple comparisons of contrast. Humans might be good at recognising faces, but computers are good at doing simple repetitive tasks very quickly.

OpenCV includes a pre-trained face detection model based on many thousands of images, so you don’t have to start from scratch. As a result it’s surprising easily to create your own script and start finding faces.

I’ve created a simple online demo where you can play with OpenCVs facial detection functions without any coding.

- Go to my demo page. A sample image will load – click Find faces and see what happens. (You can click Reset to load a different image.)

- Now try adjusting some of the parameters available in the dropdown boxes to the right of the image. Click Find faces again after each change.

- Keep fiddling to refine the accuracy of the facial detection process – can you get get rid of all the false positives?

- For something different, try selecting ‘eye’ or ‘mouth’ from the ‘Classifier’ list.

Now you’ve got an idea of how it works, let’s try an experiment.

- In a graphics program draw a simple face like my example above.

- In my demo under ‘Your image’ click on Choose file to select your drawing (it should be in jpg or png format).

- Click Find faces to upload your drawing and look for faces.

- Was your face detected? Try changing some of the settings.

- Try some more faces. What works and what doesn’t? How weird can you make your faces and still have them detected?

- Once you have a successfully detected face, grab a screenshot of it in the demo app.

Portfolio alert! Save the screenshot of your successfully detected face in your portfolio.

As you can see, there’s no magic here – like my redaction finder it’s just a matter of breaking down a complex task into a series of simpler tasks.

Creepy or compelling?

You’ve already seen the results of some of my early experiments in facial detection. As you would’ve read in my People Inside chapter, the wall of faces from ST84/1 was my first attempt to find faces in cultural heritage collections. Since then I’ve tried a few other things:

-

Eyes on the Past – I found faces in Trove newspaper articles, and then found eyes in those faces (yes OpenCV also includes an eye classifier!). The result has been variously described as beautiful and creepy – so I figure I must be doing something right.

-

The Vintage Face Depot – What can I say? Tweet a photo of yourself to @facedepot, marvel at the transformation! In both Eyes on the Past and the Vintage Face Depot I’m using faces as a way of exploring the types of connections we make with the past.

- Eyes on the Past and the Vintage Face Depot use faces harvested from Trove. You can download a complete set here, or make use of my custom Face API!

My fiddling about with facial detection is all pretty basic. Nowadays there’s money to be made in offering these sorts of image recognition services, so the tools are becoming much more sophisticated. If your business needs to process lots of photos, it can make use of custom APIs created by companies like IBM and Face++

They do, however, provide some neat little demos that we can play around with.

-

Go to the Face++ demo site.

-

There are a number of potted examples you can try, just click on a face.

-

You can also supply a url, or upload an image. Find an image on the web and try it out.

-

You’ll notice that this service does more than just detect a face – what other information does it provide?

How do you think businesses might make use of this sort of data?

I said that recognising faces was much harder than just detecting them. However, there’s been significant advances over the last few years. The development of neural networks – computer applications modelled on the brain – have greatly improved the range and accuracy of machine learning.

Google and Facebook are investing a lot of effort to bring facial recognition up to human-like levels of accuracy. In 2014, Facebook announced that its ‘DeepFace’ system had reached an accuracy of 97.35% – close to humans. What did they train their neural network on – perhaps it was you! One advantage the Facebook research team had was access to millions of identified photos of people – Facebook users. Yep, that’s one of the potential uses of your data you agreed to when you signed up.

But not to be outdone, in 2015 Google announced it’s ‘FaceNet’ system had reached a new record accuracy of 99.63%! It should be noted that these accuracy figures are against one particular set of celebrity images harvested from the web – I’m not really sure how we’re meant to interpret them.

There’s a nice summary of facial recognition developments in this article from Science – ‘Facebook will soon be able to id you in any photo’.

How might these sorts of technologies be used in cultural heritage? In 2015 it was announced that a research team had used facial recognition to ‘identify’ a new portrait of Anne Boleyn. Given that the recognition system was trained using this medal, the only undisputed image of Anne Boleyn, I can’t help but be a bit sceptical.

You can certainly see how large photographic collections could use this technology to find previously unidentified images of particular people. Can you think of other possibilities?

Another area in which neural networks having been making rapid advances is in adding subject tags or descriptions to images. Last year Google released details of its latest image captioning system. Against a set of test images it achieved an accuracy of 93.9%. But not only does it detect the subjects of an image, it writes a caption in natural language. Once again, this model has been trained on a set of images manually captioned by human beings, but Google claims it can go beyong merely applying the same captions to new images, it can identify wholly new contexts.

Issues and dangers

Are you creeped out yet? There’s certainly something disturbing about these technologies, particularly when it comes to rapid advancements in facial recognition. If Google and Facebook are doing it, I think we can safely assume that governments are investing in similar sorts of systems. Indeed, in 2015 the Australian government announced that its ‘newest national security weapon’ was a national facial recognition system linking up existing face-identified databases, such as car licences – it’s called ‘the Capability’.

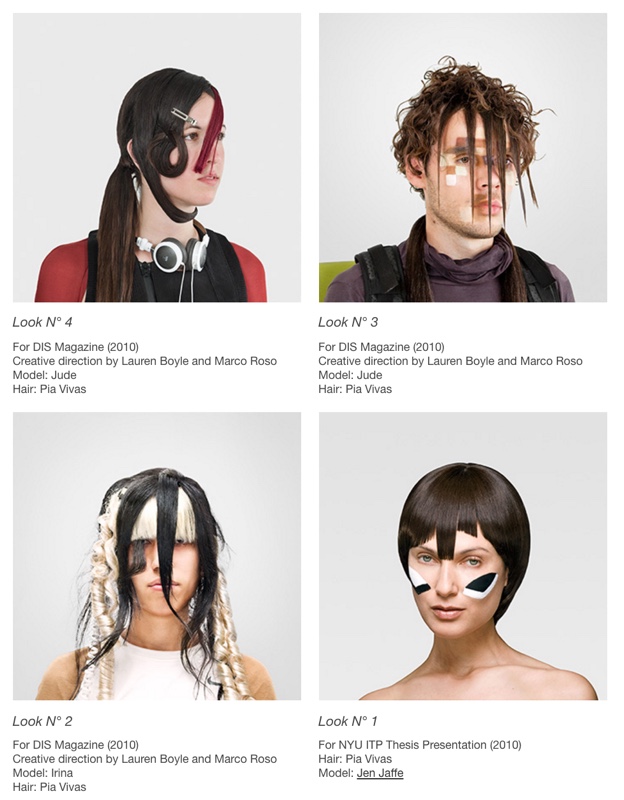

Never fear, if you want avoid identification on the street, you could adopt one of these new fashion styles, specifically designed to confuse facial detection systems.

But it’s not just identification. You may have noticed that the Face++ demo returned information on your sex, whether you’re smiling, and your race. There have been studies examining it’s possible to detect a person’s sexuality from their face. If we, in the cultural heritage sector, are going to make use of these sorts of technologies I think we need to be aware of the political and social implications of using faces as a means of assigning people to categories.

Similarly, it’s easy to see how automated image tagging could be of immense value to cultural heritage organisations that never have enough money to describe all of their holdings. But once again we have to be wary. A couple of years ago Google’s photo app caused considerable controversy when it’s automatic tagging system labelled African-American people as ‘gorillas’. It’s not that the image recognition systems are racist, but there are always likely to be biases in the image sets we use to train them. Just recently a researcher noticed that his image recognition system tended to associate images of kitchens with women. When he investigated he found gender biases in the datasets used to train the program:

Machine-learning software trained on the datasets didn’t just mirror those biases, it amplified them. If a photo set generally associated women with cooking, software trained by studying those photos and their labels created an even stronger association.

We have to always be thinking about the judgements implicit in the development of these sorts of systems. We can’t accept them uncritically.

Portfolio alert! Based on the readings and example above I’d like you to reflect (minimum 500 words, not including Harvard style references) on the sorts of data these technologies generate, and how they might be used. Are you excited or concerned? Clearing there are interesting possibilities, but how do we take advantage of them while remaining wary of their assumptions?

Train your own machine

Once again, image tagging and recognition are being marketed to business as a way of extracting useful information. Let’s try using these forces for good, and see if IBM’s demo system can help me sort my redactions from the false positives.

I’ve prepared three zip files:

- Positive examples – these are redactions I’ve checked

- Negative examples – these are false positives

- Assorted examples – these are a mix we’ll use to test our classifier

Download all the files. You can unzip the ‘Assorted’ examples, but you don’t need to worry about the others as we’ll upload the zip files directly.

-

Go to the IBM demo page.

-

Have a play with their potted examples to see the sorts of classifications that are possible.

-

Now click on the ‘Train’ tab.

-

Once again they have some potted examples that you can play around with – feel free to try them out.

-

Now let’s make our own classifier! Click on the square under ‘Use your own’.

-

Under ‘Positive classes’ select and upload the

positive.zipfile. -

In the text box give your positive examples the name ‘Redactions’.

-

Under ‘Optional negative classes’ select and upload

negative.zip. -

In the text box give your negative examples the name ‘Non redactions’.

-

Click on the ‘Train your classifier’ and wait. It could take a minute or two.

-

Once your classifier is ready you can feed it one of the images in the assorted file. Just select and upload it.

-

The classifier will tell you whether it thinks the image you uploaded is a redaction or not. Was it right?